For the modern believer to understand the present church circumstance and predict the Church’s possible future state, a careful analysis of the Church’s historical context is critical for the correct application. By applying their research, the Church identifies and may find alternate paths in its interaction with the surrounding culture and society. A critical timeframe to study for a better understanding of the American Church’s modern political and societal interaction is an age commonly referred to as “European Christendom.” In that study, the contemporary believer derives strengths and failings from the close ties between the secular and the spiritual guidance vital for effective evangelism in the post-modern cultural context.

As the political power structure of the Roman empire shifted from Rome to Constantinople under Emperor Constantine, the separation between the western and eastern parts of the empire began to deepen under their distinctive differences, including language, theology, and hierarchy. Within the political vacuum left by the shift east, Rome’s papacy began to exact increasing influence over society in all aspects, both spiritually and culturally. With each successive Pope, this influence increased until its apex under Pope Gregory I in 590. Under Gregory, the papacy’s accomplishments were exquisite. He founded monasteries, wrote a biography of Benedict boosting monastic ideals throughout the western Church, elevated hymns to prominence within the liturgy, reformed the Church of the West’s missionary strategies, and rallied the Romans in defense against the invasion of the Lombards.[1] Mark A. Noll, in his work Turning Points: Decisive Moments in the History of Christianity, states, “The crowning glory of Gregory’s pontificate was that somehow, despite the immense responsibility that poured from every direction into his hands, he seems to have remained a humble, pious Christian.”[2]

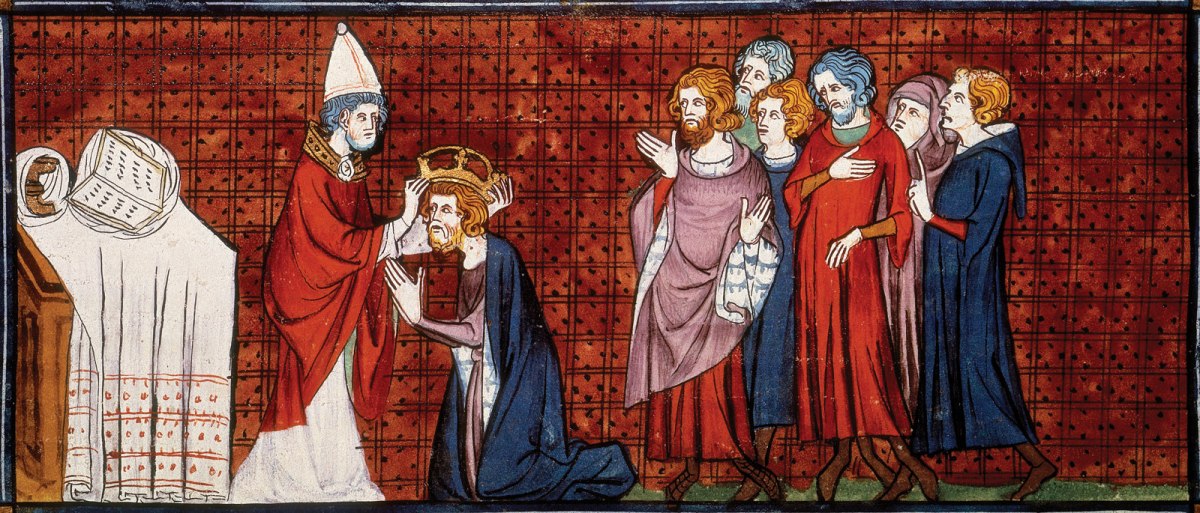

In addition to the rise of the papacy, the influence of Islam’s spread further alienated the Western Church from the Eastern empire, leading to an increasing reliance and engagement with the northern kingdoms of Europe. Against the backdrop of these various factors, the compact of power reached its zenith with the crowning of Charlemagne by Pope Leo III on Christmas Day in 800.[3] Thus began the collaboration of Church and State that continued throughout the Middle Ages with its remnants still evidenced in Europe today. The historical analysis of this rise in Christendom resulted in several evidentiary examples of weakness in this arrangement. With humanity’s fault and the propensity toward power and prestige, the modern student surmises the resulting tragic endeavors as a products of the compromise of power: the Crusades, the sale of indulgences, the harsh punishment of heresy through the Inquisition, as examples. Though there were periods of renewal primarily through monastic endeavors during the Middle Ages, the overarching theme is one of distraction from the core mission of the Church as commissioned by Christ in the gospel of Matthew, “Therefore go and make disciples of all nations, baptizing them in the name of the Father and of the Son and of the Holy Spirit, and teaching them to obey everything I have commanded you. And surely I am with you always, to the very end of the age” (Matt. 28:19, NIV).[4]

In the modern American context, the weaknesses of political and cultural collaboration are evident. Whether the engagement with power comes from the political “left” or “right” of the spectrum, the same distractions impinge upon the Church’s core mission and compromise its witness within the culture. The modern believer maintains their influence by living out the example of Christ in a cultural context without compromising for the impact that power may promise. Once the Church is wedded to a political ideology or cultural norm, the negative aspects that arise inevitably from the fallen state of humankind tarnish the Imago Dei visible to the modern culture. Paul, in his letter to the Galatians, alludes to the idea that allowing just a little delusion or compromise into the ecclesia endangers the entirety of the fellowship, “That kind of persuasion does not come from the one who calls you. A little yeast works through the whole batch of dough. I am confident in the Lord that you will take no other view. The one who is throwing you into confusion, whoever that may be, will have to pay the penalty” (Gal. 5:8-10).

Bibliography

Noll, Mark A. Turning Points: Decisive Moments in the History of Christianity. 3rd ed. Grand Rapids, Mich.: Baker Academic, 2012.

[1] Mark A. Noll, Turning Points: Decisive Moments in the History of Christianity, 3rd ed. (Grand Rapids, Mich.: Baker Academic, 2012), 105.

[2] Ibid, 106.

[3] Ibid, 112.

[4] Unless otherwise noted, all biblical passages referenced are in the New International Version.